Russian Rockets: How Moscow Uses Advertising to Prop Up Its Space Industry

The bill presented to the Duma in early October marks a turning point in Russian space policy. It allows companies to place their logos and slogans on launch vehicles and rockets produced by Roscosmos and its subsidiaries, notably Progress and Khrunichev.

Faced with Western sanctions and a shrinking defense budget, Russia is now allowing advertising on its rockets. Behind this project lies a strategic objective: to ensure the industrial continuity of the Russian space complex and maintain its technological sovereignty despite isolation. The official objective is to “diversify revenues” in a sector that has been weakened since the war in Ukraine and the restrictions imposed by the European Union.

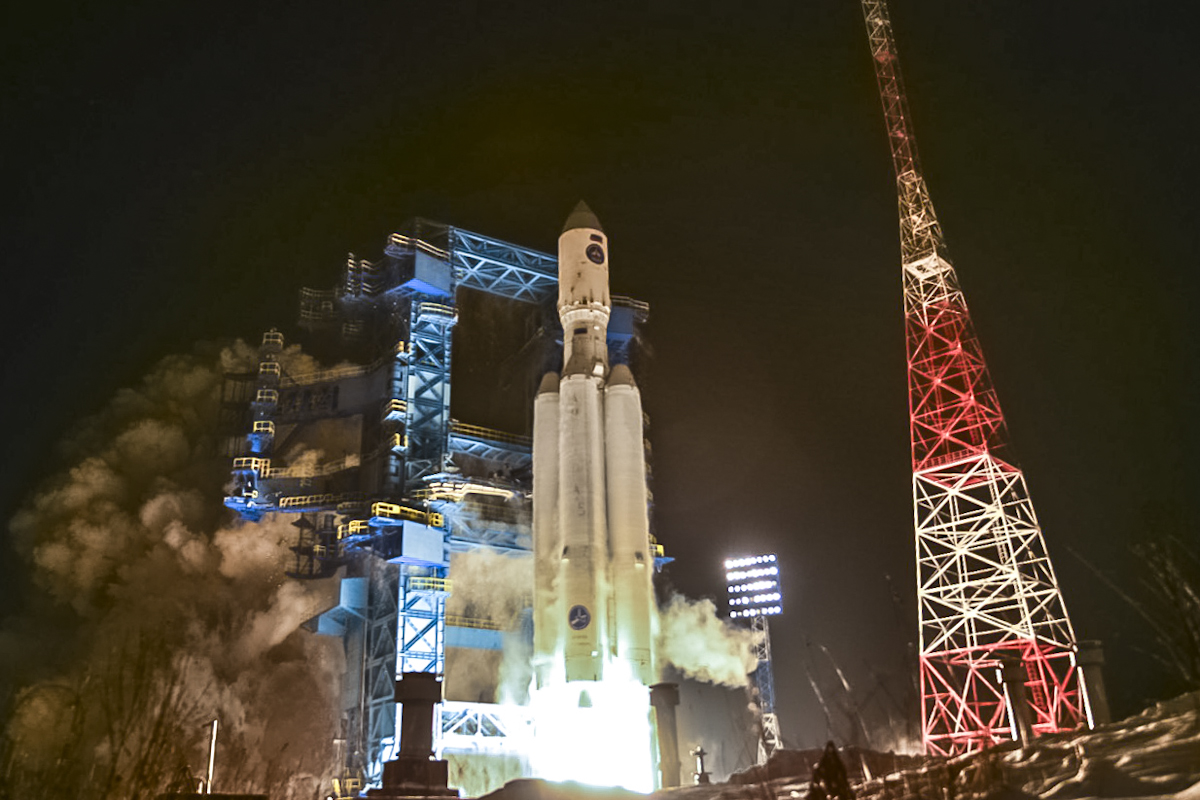

The measure aims to finance the maintenance of strategic infrastructure, in particular the Baikonur cosmodrome, which costs around $115 million per year to lease from Kazakhstan. Ultimately, these advertising revenues could contribute to the development of the Vostochny site, which is intended to gradually replace Baikonur in the Russian space logistics chain. Russian officials also hope to attract private investors to a sector that has so far been dominated by the state. By allowing national brands to sponsor missions, Moscow is seeking to transform its Soyuz and Angara rockets into visible symbols of technological power, while reducing dependence on public funding.

Behind this decision lies a broader issue: that of information and symbolic warfare. By displaying visible logos during its launches, Russia is turning each rocket launch into an act of geopolitical communication. Space, already militarized and saturated with observation satellites, is also becoming a medium for projecting the national image. Experts at the Skolkovo Institute and the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT) have estimated that an “orbital advertising” campaign could generate up to $2 million per day under optimal conditions, an unprecedented return for an activity once reserved for research and defense.

This prospect appeals to a Russia seeking financial autonomy. The revenue from these rocket advertising contracts could fuel the financing of dual-use civilian and military programs, such as the Gonets telecommunications satellites or the Resours-P and Araks observation constellations. In other words, orbital marketing could become a discreet lever in Russia's defense strategy. Weakened by sanctions, Roscosmos has lost access to several critical European components, particularly in the fields of avionics and cryogenic propulsion. By resorting to private funding, the agency hopes to maintain a production rate compatible with the country's military needs. The Angara-A5 rockets, in particular, are designed to place satellites belonging to the Russian Ministry of Defense and the GRU (military intelligence) into orbit.

This commercialization of rockets raises questions: to what extent can a strategic space program lend itself to market logic? Observers see this as a form of privatization of technological deterrence, a development that Moscow fully embraces in the context of prolonged war. Researchers involved in the project acknowledge that each advertising satellite will have to be “massive” in order to reflect enough light and remain visible from Earth. This technical challenge is in line with the visibility and reliability requirements specific to military applications. In short, the progress made in orbital advertising could indirectly enhance the performance of Russian space surveillance systems.

While the economic benefits are still hypothetical, the political gains are clear. By displaying its national brands in space, Russia is asserting its industrial resilience and strategic independence from Western powers. The project could also stimulate subcontracting chains in the military-industrial complex, from Voronezh to Omsk, where RD-107 and RD-191 engines are produced. However, criticism persists: Proton-M rockets continue to use toxic propellants (UDMH and nitrogen tetroxide), whose emissions—up to 450 tons per failed launch—poison the Kazakh steppes. For Moscow, the transition to environmentally friendly propellants remains too costly as long as financial resources depend on advertising revenue.

This strategy, halfway between alternative financing and space diplomacy, reflects the transformation of a defense industry in search of unconventional economic support. Russia is turning advertising into an instrument of sovereignty.